Professor Carolyn McKinney from University of Cape Town visited the School of Language and Translation Studies in April and observed the difference between learning facilities in South Africa and Finland. In South Africa, Prof. McKinney is working in small intervention projects in schools to look at what is possible.

Professor Carolyn McKinney from University of Cape Town in South Africa visited the School of Language and Translation Studies at the end of April. During her visit, she gave a presentation drawing on her recently published paper that dealt with the coloniality of language, and emergent bilingual children’s writing in a South African school. She also acted as the opponent for Soili Norro’s dissertation defense at the Faculty. Norro’s research is based in Namibia, and McKinney was one of her pre-examiners.

“Norro’s thesis dealt with the perceptions that Namibian primary school teachers had about languages of teaching. Namibia was a colony of South Africa, and they have similar policies,” McKinney explains.

During her visit, Norro also took McKinney to a couple of schools to follow lessons. McKinney observed the difference between learning facilities in South Africa and Finland.

“It is from one extreme to the other – the desert to the Amazon forest in terms of the resources and what’s possible. Also the degree of choice the students have in terms of putting together the curriculum,” says McKinney.

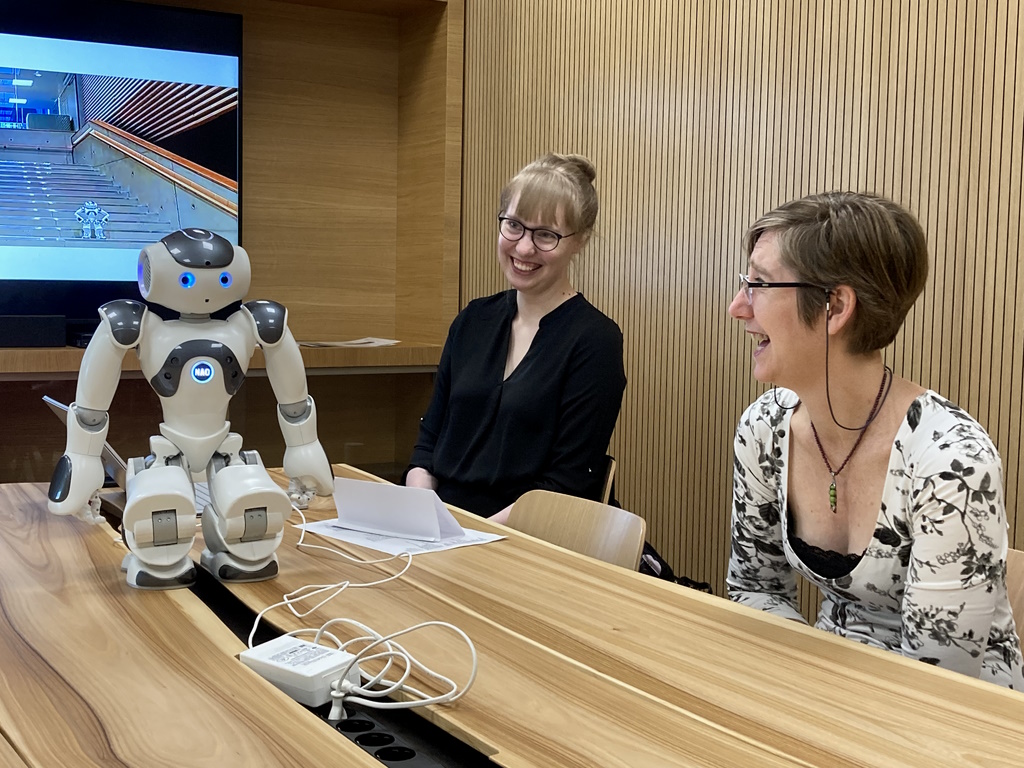

Research Assistant Hilla-Marja Honkalammi introduced McKinney to the language learning and social robot of the RoboLang research project. Photo: Minna Nerg / University of Turku.

From the language learning and teaching perspective, the textbooks are used bilingually in Finland, whereas in South Africa the language teaching is unilingual. For the students to work independently is difficult.

“[During the school visit] it was lovely to see the engagement of the students who were learning English, being able to communicate with each other,” McKinney says.

In South Africa, the context is very different from Finland, as monolingualism is not the norm.

“It is normal to speak more than one native language. Yet there is a very strong idea that monolingualism in English is preferred,” McKinney states.

Multilingual materials have always existed

According to McKinney, there are deep-seated beliefs in the idea of Africa as uncivilized. These result in essentially racist language ideologies.

“There have always been people who are avant-garde and resisting, and it is because of them that there are materials that show that. But they cannot be rolled out in schools, they need to be developed,” McKinney explains.

McKinney tells about a colleague Dr Xolisa Guzula who has translated dozens of children’s books into her native language isiXhosa. One of the books is Stephen Hawkins’ and his daughter’s book “George’s Secret Key to the Universe”. There are also people who have written theses in African languages.

“The biggest challenge is changing the beliefs. Resources and money are made available, when people believe,” says McKinney.

Experimenting with bilingual materials in schools

McKinney’s lecture at the Faculty featured the concept of ukuzilanda. This was being developed by her colleague Dr Athambile Masola who in her PhD thesis looked at the erasure of African women’s writing.

“Ukuzilanda literally means to fetch oneself. It’s about fetching one’s past and bringing it into conversation with the present. There is an isiduko practice where African families can recite their clan names,” McKinney explains, “bringing their histories into the present”.

“In the case of women’s writing, it is fetching that history and making it visible. It’s not as if it doesn’t exist,” McKinney continues.

Professor McKinney and her colleagues have developed experimental bilingual Xhosa and English materials to be used in schools. Photo: Minna Nerg / University of Turku.

McKinney herself is working in small intervention projects in schools to look at what is possible. She and her colleagues have developed some experimental bilingual Xhosa and English materials. In order to have the teachers to use those texts, they invited the parents to discuss the place of African languages in the classroom.

“If you reach out to parents, they are incredibly supportive. In the short term, in order to change perceptions, we are working with schools to help the teachers understand. My students are working on what can be done outside of school,” McKinney says.

The team have put together an advocacy collective titled “bua-lit” “Language, literacy and social justice”, pulling together resources from different teachers who are passionate about promoting African languages. Television and media comments and presentations in school are also on the agenda.

“The change cannot be topped down. When finally the government resources African languages in education, people must be ready,” McKinney concludes.