From a Researcher: Pussy Riot's Background Dates Back to the Russian Feminism

Feminism has found the strongest footing in the artistic and scientific communities in Russia. – The tighter the control, the more radical and spontaneous the protests have become, writes Associate Professor in Sociology Suvi Salmenniemi.

Russian feminism began when Anna Filosofova, Nadezhda Stasova and Marija Trubnikova established the ”Society for Cheap Lodging” in the mid-1800s, which offered housing and help in childcare as well as sewing work for poor women.

At the end of the century, Filosofova and Stasova were among the founders of “Russian Women’s Mutual Philanthropic Society” which grew to be the most significant feminist organisation of Tsarist Russia. It helped women to find employment, provided housing and healthcare and participated in the struggle for women’s suffrage.

Women’s rights were also a central part of the underground socialist revolutionary movements born in the 19th century, but after a while its significance waned in the movement’s operations. However, there was a considerable amount of women in the movement and especially in its terrorist faction. Radical women dedicated themselves to the political objectives and devoted their personal lives to them.

Women’s Movement Was Divided into the Moderates and Radicals

Russian culture, especially its Orthodox feature, offered the women a cultural model for self-sacrifice and asceticism, which the Soviet Union also encouraged the women to cherish later on. This model of self-sacrifice on the one hand oppressed women as it often required them to give up a great deal and make extreme choices but on the other the thought of women’s moral superiority which was linked to the model opened up new opportunities for action.

Russia’s first openly feminist political organisation, the League for Women’s Equal Rights, was founded in 1905 and a few years later the All-Russian Women’s Congress was established on its basis.

However, social class and the ideas of the goals and the ways to achieve societal change divided the women’s movement. The political agenda of the feminists was liberal and moderate: they concentrated on improving women’s position and fought their cause by peaceful means.

As for the Marxist radicals, instead of gender, they saw the social class as a primary mechanism of oppression. According to them, women’s emancipation would only take place if the oppression based on class was abolished.

Women Seen as a Threat to the Spread of the Revolutionary Ideology

The Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 had a dual impact: on the one hand women finally gained the sought-after suffrage, but on the other it also meant suppressing the feminist organisations. For decades onwards, feminism became a politically dubious “bourgeois ideology”.

All social organisations were subjugated by the Communist Party to implement the policy it dictated. In 1919, the Party established women’s department Zhenotdel, the purpose of which was to spread the ideology of the revolution amongst women.

According to the Bolsheviks, the department was needed as women were considered politically more backward than men and therefore as a threat to the societal change. In 1930, Stalin declared that “women’s issues” had been solved for good and Zhenotdel was shut down.

Maria Club Was Persecuted in the USSR, Perestroika Allowed Public Debate

In the Soviet Union, there were efforts to organise social activity independent of the state and to question the official political line. These kinds of dissenting societies, which were severely oppressed, were formed particularly from the late 1950s onwards.

A group of dissidents formed by artists in Saint Petersburg tried to invoke critical discussion on women’s issues and to bring out the flip side of the Soviet equality policy.

In 1980, women published an underground magazine called Maria and established an unofficial women’s club of the same name. The central figures of the group were soon targeted by the authorities and exiled from the USSR to the West right before the Moscow Olympics in 1980.

Maria Club held out a few years until it was silenced for good. Some of the members fled abroad, some were harassed by terminating employment and confiscating their apartment as well as by threatening with the custody of their children. One of the most active members of the group was sentenced to prison for several years.

It wasn’t until the perestroika and glasnost policy initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev that feminist thinking broke its way to public debate. However, perestroika did not only give voice to feminist criticism but also the patriarchal rhetoric was strengthened in the discussion. In the public debate, women were encouraged to withdraw from the working life back to the warmth of the hearth.

At the end of the 1980s, the feminist women’s movement activated as a part of the larger movement that was aiming at democracy. Several women’s organisations were founded and networks that connected Russian and Western activists were created.

Organisations under the Government’s Microscope, Rebellion Simmers at Grass Roots Level

The 1990s can be called as “the decade of the gender” with good reason, so actively the new women’s movement emerged in Russia. Instead, the Russia of the 21st century swears in the name of stability and state-controlled reforms.

The government has strengthened the supervision of societal movements and civic organisations and strived to direct their development more energetically than before. At the same time, foreign funding for civic activities has reduced significantly and cooperation between Russian and Western activists has become more difficult.

In Russia, feminism has remained as a movement of a small community of experts and scientists and it has not become a societal movement that gathers extensive numbers of followers. However, at the same time as many of the women’s organisations established in the 90s have been caught up in trouble and their activity has faded away, a novel type of grass root feminist activism has sprouted in Russia.

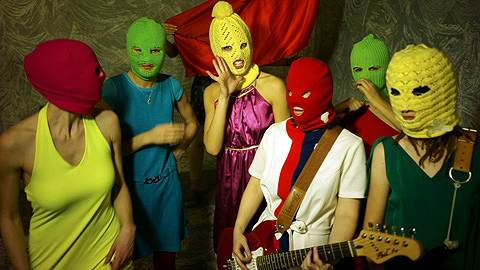

One example of this ”new wave” feminism is Pussy Riot, the Muscovite feminist collective who became known in February 2012 for the “punk prayer” criticising Vladimir Putin, performed at a church in Moscow. Three of the members were arrested and two of them were convicted.

Pussy Riot’s fate bears resemblance to that of Maria Club 30 years earlier: each group’s political protests were suppressed by force. The fate of these groups shows how feminism is political dynamite in Russia.

It also demonstrates the historical continuum of feminist struggle and how each generation of women in its turn tests the boundaries of authority, freedom and resistance.

Suvi Salmenniemi

The writer is Associate Professor in Sociology at the University of Turku.

Photos: Igor Mukhin, Erja Hyytiäinen

Translation: Mari Ratia