Researchers from Turku Are Looking for a Treatment for Secondary-progressive MS

Researchers at the Turku PET Centre are looking for functional approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis which currently has no treatment available.

At the Turku PET Centre, a pioneering research is done to improve the diagnosis and to develop a treatment for secondary-progressive MS. The research is conducted in cooperation with researchers from universities in New York and London.

For nearly twenty years, there have been treatments for relapsing-remitting MS that prevent the relapses of worsening neurological function. In this form of the disease, the patients have relapses that occur, for example, once a year and between the attacks they are in remission for long periods of time.

– However, there is a blind spot: there is no effective treatment for secondary-progressive MS. We cannot give patients any help that would affect the progress of the disease, says Docent Laura Airas from the University of Turku, who is the leader of the research group.

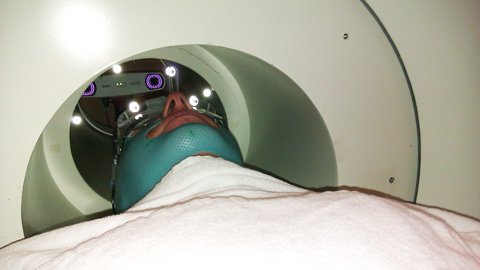

The research group led by Airas includes ten people and they are striving to change the situation. They started using positron emission tomography (PET) in their research and it has revealed more about MS than magnetic resonance imaging, which is usually used in neurological research.

– We are trying to find out the origins of the disease, to develop the methods of diagnosis, to recognize possible treatments and to test them, says Airas.

The Forms of MS Progress Differently

MS is a disease of the central nervous system, i.e. brain and spinal cord, where the immune system operates abnormally and attacks the body’s nervous system. Typically, people get the disease already in their thirties and the symptoms include muscle weakness and stiffness, walking difficulties, dizziness and loss of balance, double vision, lack of coordination in the extremities, bladder and bowel problems, and fatigue.

– For 85 per cent of the patients, the disease starts with attacks and they have relapses maybe once a year, but no symptoms during the remission. However, about 15 per cent of those suffering from MS have no relapses but the disease progresses steadily, says Airas.

Also for most patients who have relapsing-remitting MS, the disease later transitions into secondary-progressive MS.

In relapsing-remitting MS, inflamed immune cells from the peripheral immune system cause inflammatory attacks on the central nervous system. The access of the inflamed immune cells to the brain can be prevented with medicine and injections which help to decrease the harmful effects of the inflammations on the central nervous system.

In secondary-progressing MS, the inflammation starts to live its own life in the central nervous system and there are no effective treatments for it. Magnetic resonance imaging, a great tool in examining relapsing-remitting MS, does not reveal all the inflammation that is related to the secondary-progressive form and it can only be seen with a PET scan.

– PET scans give us a chance to visualise the different aspects of neuropathology, says Airas.

The Microglia Change, But Why?

One of the changes revealed by the PET scans happens in the microglia cells of the brain. In normal circumstances, microglia clear harmful substances and cellular debris from the brain. In a healthy brain, about 10 per cent of all the brain cells are microglia. However, in MS, they change their shape and activity and activate for an unknown reason.

– We know from neuropathological research that the further the disease has progressed the greater the microglia activity is. We want to know how a useful, debris-clearing cell transforms and becomes harmful with the inflammation and what kind of an effect does this have on the disease process, for example, on the development of neurodegeneration, says Aira.

The research has also advanced with the commencement of animal model trials that began three years ago.

– By using the animal model of secondary-progressive MS, Turku is the first place in the world where it has been proven with in vivo PET research that MS medication decreases the microglia activity, says Airas.

Text: Erja Hyytiäinen

Photos: the research group, Erja Hyytiäinen

Translation: Mari Ratia