In the Academy of Finland PostDoc project JuDiCe (Justice in Digital Spaces), which has started in fall 2022 at the Faculty of Law, docent and PostDoc researcher Miriam Tedeschi will find out how justice, urban space and tech are interconnected in people’s everyday life.

On September 1st, 2022, the three-year Academy of Finland PostDoc project JuDiCe started at the Faculty of Law of the University of Turku, led by docent and PostDoc researcher Miriam Tedeschi. The project aims to create a new theoretical framework that combines theories of justice with the blended (physical/digital) urban space.

Tedeschi has always worked in-between disciplines. She has a Ph.D. in Regional Planning and Public Policy. She spent her doctoral studies (2014–2016) between the Department of Design and Planning in Complex Environments of the University Institute of Architecture, Venice and the Law & Theory Lab of the University of Westminster, London. After that, she moved to Finland as a PostDoc researcher at the Department of Geography and Geology of the University of Turku. Her multidisciplinary curriculum is completed by an MA in Philosophy and a specific expertise in the ICTs, where she worked as research-oriented consultant for 15 years prior to her Ph.D. The project that has just started brings together all these places and disciplines.

– Sometimes it is not easy to be in-between disciplines, but this Academy project is a truly interdisciplinary effort. It has proven to be a risky but successful endeavour, says Tedeschi.

In scientific research, concepts are transmitted first and then further refined. At times they start living their own independent life. Tedeschi’s research and theoretical approach were heavily influenced by the concept of lawscape developed by her Ph.D. supervisor, Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, Professor of Law and Theory and Director of the Law & Theory Lab of the University of Westminster.

– Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos coined the concept of lawscape. It means that it is not possible to have law without space, or space without law. This strongly affected my own thoughts and way of seeing reality, right at the beginning of my Ph.D., says Tedeschi.

In 2021 Tedeschi was still working at the Department of Geography and Geology of the University of Turku and joined the Faculty of Law part-time. There she started elaborating on theoretical questions of legal geography, specifically thinking about how law, code, and space could be combined from a new materialist perspective. In that context, the idea of an Academy project was born.

– I find the science of space (geography) and justice complementary, and cannot think the former without the latter anymore. In geography, I gained a lot of experience in terms of how empirical work needs to be designed and carried out. On the other hand, joining law in UTU made it possible to go more in-depth into philosophical and theoretical thinking.

In urban space, physical and digital overlap

There is still the tendency to think that in the urban space the physical and the digital are two separate dimensions. But the city doesn't work like that – they overlap in the urbanites’ everyday life. According to Tedeschi, we should understand urban space as a whole, where both dimensions overlap and intersect.

From a legal thinking perspective, law and justice are also something that happens in-between the physical and digital space. Tedeschi offers a practical example.

– Imagine that you live in a certain physical location or neighbourhood, which is marginalised or stigmatised, or that you visit there often. You may share this information via social networks, and people might get to know that you belong to this neighbourhood that does not have a good reputation. This can become a problem when it comes to spatial justice and to the right not to be discriminated in the urban space. When you share this information in social media, you may get negative reactions in return, and wrong or offensive assumptions may be made about, for example, your ethnicity or economic status. This materially affects one’s life, describes Tedeschi.

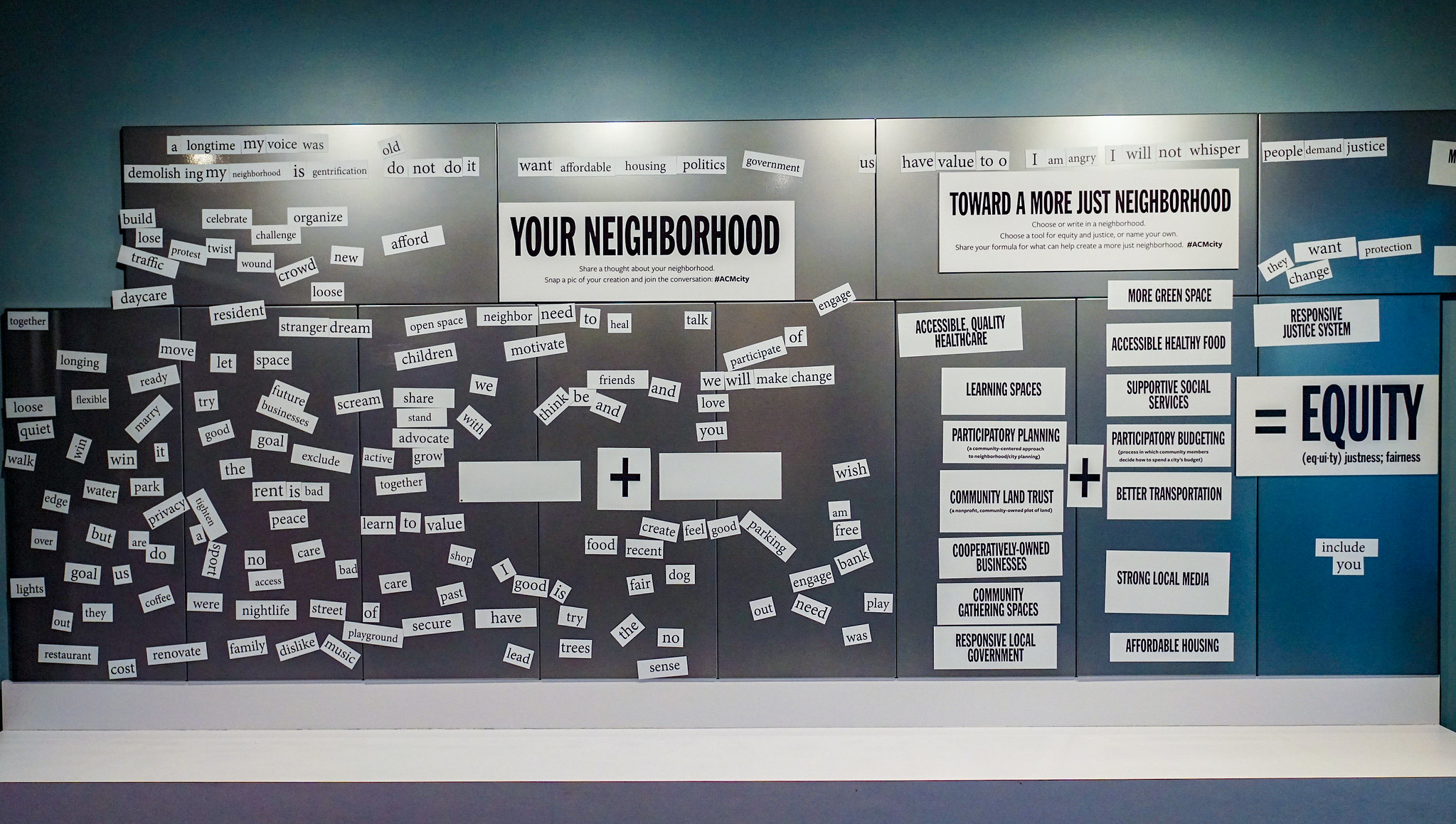

A Right To The City by Ted Eytan / Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

According to Tedeschi, there is a connection between someone sharing information in social media about living/visiting somewhere and the independent life that this piece of information starts living. A data-double is created in the digital space, and may (mis)behave independently from us. It is by no means treated or experienced in a neutral way. In this in-between space, justice happens, or it doesn’t.

Thus, urban space is not a neutral element, but moral values and power are always associated with it. Injustice happens in space, and in the digital dimension it may be amplified: it becomes real both offline and online.

Students will experience justice with their bodies

JuDiCe, which has just started, not only is a research project, but has also an educational aspect, as there is the plan to carry out, among other things, fieldwork with students. The purpose of this is to raise students' awareness of how justice is embedded in urban space, and how the so-called data-doubles have effects on how they experience it. Data-doubles refers to digital copies of people – all of us – that are stored in different data and information systems.

– The first edition of the introductory, experimental course ‘Law and the Urban’ is now open to both law and geography students at the Faculty of Law. There will be another course in the fourth period, in spring 2023 (‘Looking for justice: Law, power and the digital city’), where these topics are explored more in depth. The focus is on law students: the purpose is for them to experience law and code as material and spatial elements. And, on the other hand, geography students will be asked to explore how law is embedded in urban spaces, and is influencing their movements – which is also what legal geographers do, states Tedeschi.

At the end of the project, a data-spatial justice manifesto will be planned with the students based on their inputs.

The courses use a mixed-method approach and combine theories of spatial justice with diaries. In the diaries, the students will reflect on their experiences of the data-doubles in the urban spaces.

– For example, we will critically discuss some urban interventions in terms of crime prevention, and how they are leading to discrimination of specific groups of people in the urban field. Students will be asked to experience all this with their own bodies, and in relation to the technological devices that they are using. With the courses, they also get to explore the city, says Tedeschi.

Law – challenging abstract approaches and exploring the affective and emotional dimensions

Tedeschi says that, when she was visiting doctoral researcher at Law & Theory Lab of the University of Westminster, one of the exercises that, she found out, her Ph.D. supervisor, Prof. Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, asked the students of his Law and the Environment course to do, was to go out in London and take ‘walks in the lawscape’ (as it is reported in his ground-breaking book from 2015 Spatial Justice: Body, Lawscape, Atmosphere). In a big city like London law is materialized and experienced with the body in many different, unpredictable ways: by imperceptibly reacting to CCTV cameras or security measures, or by being uncertain as to what to do and how to behave in privately-owned public spaces (POPS). And what happens if you try to escape the lawscape? This is what Prof. Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos encouraged people to do at the Venice Art Biennale, where they were experiencing how one feels when trying to flee the lawscape – for example, by moving in a different or unexpected direction than other people.

– Then people start looking at you. The law is a material layer on our bodies, and usually one would not want to act against it. If you act in strange ways in public spaces, people may think that you're anti-social or doing something illegal. Via affect and emotions, this heavily influences the way in which you move in the urban space, says Tedeschi.

A Right to the City by Ted Eytan / Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

All this has shaped Tedeschi’s theoretical thinking, which finally flowed into her monograph Crime, Bodies and Space. Towards and Ethical Approach to Urban Policies in the Information Age, published in 2019. The Academy of Finland PostDoc project JuDiCe is now this monograph’s ideal continuation, where the ‘code’ dimension is added to her initial explorations of law and the urban space.

Tedeschi reflects that we are indeed rational beings, but we are also driven by emotions and intuitions. They also guided Tedeschi in both her research path and studies.

– There are many things that are not planned and that just happen. I worked in geography for many years, and, when my PostDoc was about to finish, I thought about a project like this. I didn't think it would have actually become true, says Tedeschi.

Tedeschi reflects that it's all about seizing the right opportunity – trying something because you feel there may be something there, new, waiting for you. There are many different layers that come together and contribute to making a scientist’s path. Among them, the emotional ones should not be underestimated.

– Follow emotions or instincts. This is why I like non-representational geographies, because they work with affect and emotions. And, through affect and emotions, law, code, and space are also experienced, Tedeschi states.

> JuDiCe

> Law and the Urban course in Peppi