New international study reveals how evolution and locomotion patterns, such as bipedalism, shaped bone structures through proteins present in the bone matrix.

A new international study sheds light on the evolutionary mechanisms behind bone mechanoadaptation and highlights several protein families potentially involved in bone remodeling.

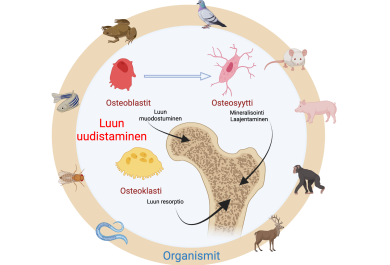

Vertebrate bones constantly sense and respond to mechanical forces, a phenomenon known as mechanoadaptation. The new study shows that this ability has been shaped not only by biomechanics but also by millions of years of evolutionary pressure related to locomotion. Species with different locomotor patterns display distinct evolutionary signatures in the genes and proteins associated with load sensing and skeletal remodeling.

The study was carried out by the Phylobone research group with researchers from University of Turku as well as the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and Ramon Llull University (URL) in Spain, and was led by Docent Pere Puigbò and Docent Miho Nakamura.

“These results indicate that the evolution of locomotion has played a major role in shaping the molecular machinery of bone mechanoadaptation. Two of these decisive moments were the transition of vertebrates from water to land, which increased the pressure on the limbs, and the emergence of bipedalism in humans, which redistributed stress between arms and legs,” says Puigbò.

The research identifies several non-collagenous proteins that may act as key regulators of mechanotransduction, many of which have received limited attention in previous skeletal studies. These findings provide new insights into how bone cells detect and respond to forces, and how these mechanisms evolved across vertebrates.

“From a cell biology perspective, our work points to important but underappreciated proteins that could be central to bone remodeling,” adds Nakamura.

The findings are important for understanding bone regeneration, fragility, and osteoporosis, and could help guide the development of biomaterials inspired by natural skeletal adaptation.

The study highlights several non-collagenous proteins, including Fetuin-A, which controls mineral deposition and prevents abnormal calcification. Fetuin-A’s conserved role is key for maintaining healthy bones and may affect osteoporosis risk by balancing bone formation and breakdown.

Building on these discoveries, the Phylobone research group—whose mission is to study bone regeneration in the light of evolution—is investigating how such proteins drive skeletal adaptation and bone remodeling.

The study, conducted on bone cell cultures and using phylogenetic analyses, was recently published in Communications Biology, a journal from the Nature group. The research was funded by the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.