According to a new study, the number of species in the wildlife trade may exceed previous estimates, underscoring the urgent need for more comprehensive monitoring systems and regulation to improve the sustainability of the trade.

According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), at least 50,000 species are involved in the global wildlife trade, contributing to people’s livelihoods worldwide.

However, while this figure staggering, it may underestimate the true scale of the issue, particularly when considering sectors such as the pet trade.

A chameleon for sale in a shop, possibly taken from the wild. Credit: Julie Lockwood

For example, recent data show that the number of butterfly species alone involved in trade exceeds the total number of terrestrial arthropod species estimated by IPBES to be involved in trade.

This raises a critical question: How many wild species are really being traded? Answering this question is no small task.

“We are still far from understanding the true scale and impact of the global wildlife trade”, says Dr Caroline Fukushima from the University of Turku, Finland.

While the trade of some species is regulated under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), most of the trade occurs outside the scope of international monitoring or legislation. A notable exception is the United States, one of the world's largest wildlife traders, where the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service tracks wildlife imports and exports through its LEMIS database.

Using 22 years of data from LEMIS, an international research team led by Professor Alice Hughes from the University of Hong Kong, and including Dr Caroline Fukushima from the Biodiversity Unit of the University of Turku, has produced one of the most comprehensive analyses on wildlife trade.

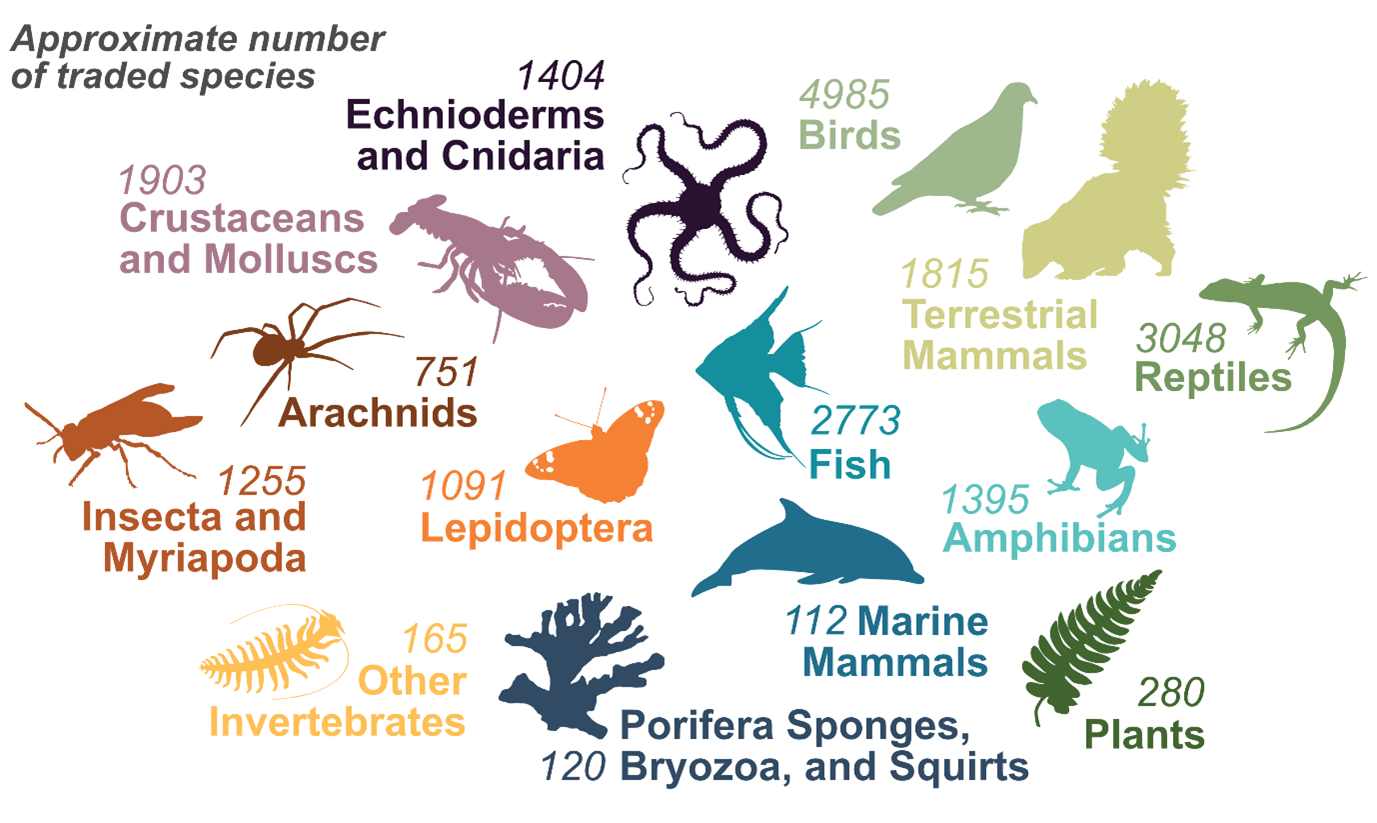

Data from LEMIS on wildlife in trade. When data from CITES is included, the total figure increases by almost 8,000, largely due to the import of wild plant species.

The findings of their research are striking:

- In over 22 years, the U.S. traded almost 30,000 wild species and over 2.85 billion individuals, among animals and plants

- In many taxonomic groups, more than 50% of the individual animals and plants were taken directly from the wild.

"Given the limited data on the trade of many groups of organisms across various regions, accurate estimations on the true number of species traded globally remains challenging. However, if the U.S. trades nearly 30,000 species, it is likely that previous global estimates of 50,000 species are significantly underestimated,” Fukushima explains.

While the LEMIS database in the United States is widely regarded as one of the most comprehensive contemporary systems for collecting wildlife trade data, other major global traders, such as the European Union, rely on systems like the Trade Control and Expert System (TRACES) which are primarily designed to address food safety concerns and cover a much narrower range of organisms. Similar gaps in data and monitoring can be seen in other parts of the world.

This also raises serious concerns about the sustainability of this trade. For most species, we also lack data on the size of wild populations or the scale of harvest, making it impossible to assess whether trade is sustainable. Alarmingly, where such assessments have been made, the populations being harvested have often shown declines.

"Our study reinforces the urgent need to improve both the collection of basic ecological data on wild populations and the monitoring and regulation of wildlife trade, especially for neglected groups like arthropods and other ‘non-charismatic’ species. Given its significant role in international wildlife trade, the European Union must take greater responsibility by implementing more comprehensive monitoring systems. Without better data and regulation, we cannot ensure that trade is sustainable or that vulnerable species are protected”, says Fukushima.

This research highlights how little we genuinely know about the scope of the wildlife trade. The lack of standardised global monitoring undermines efforts to sustainably manage wildlife trade and puts countless species at risk. The researchers encourage all the nations to assess how their own wildlife trade data is recorded and shared. Without more comparable global data we cannot assess the impact of trade on the majority of traded species.

The article was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS)

Pictures:

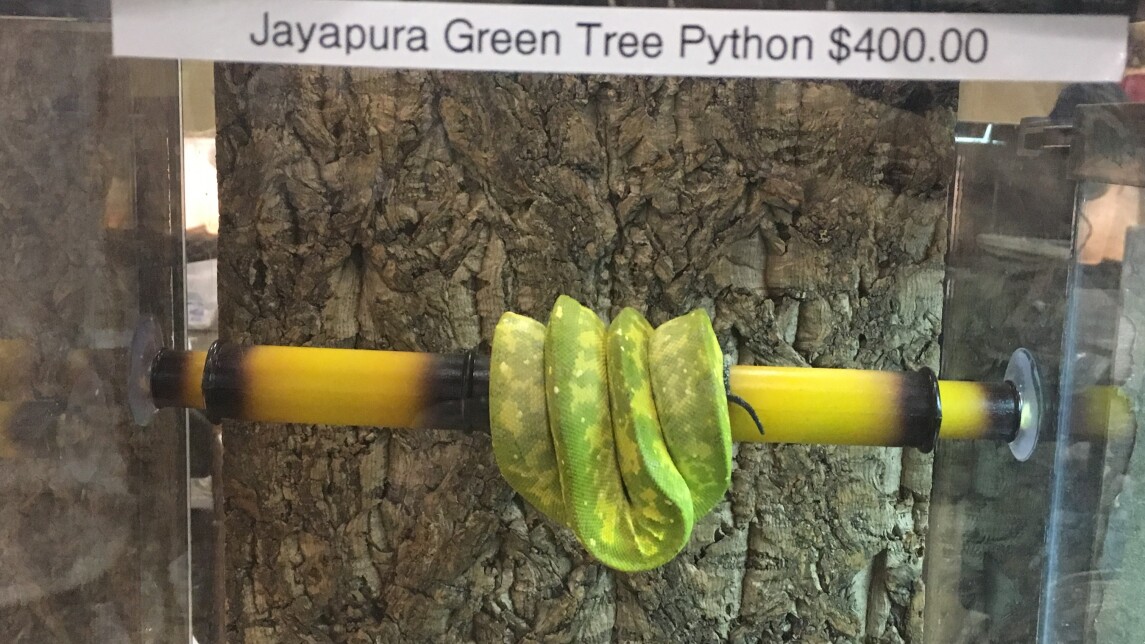

Picture 1: A striking Jayapura green tree python, likely wild-caught, highlighting the beauty and vulnerability of species in the wildlife trade. Credit: Julie Lockwood

Picture 2: Data from LEMIS on wildlife in trade. When data from CITES is included, the total figure increases by almost 8,000, largely due to the import of wild plant species

Picture 3: A chameleon for sale in a shop, possibly taken from the wild. Credit: Julie Lockwood

More information:

Caroline Fukushima, University of Turku, Biodiversity unit and the Biodiversity and Sustainability Solutions Lab, caroline.fukushima@utu.fi

https://sites.utu.fi/bisonslab/

Professor Alice C. Hughes, University of Hong Kong, achughes@hku.hk