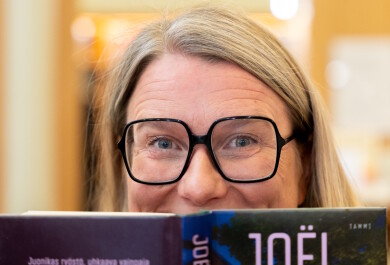

Cytomegalovirus is found in a majority of investigated cancer tumours. The mystery is why the virus appears in the tumours in the first place. Professor and InFLAMES group leader Cecilia Söderberg-Nauclér studies this pathogen that infects almost everyone at some point in their lives. Her research could bring new solutions for treating brain cancer.

Cytomegalovirus is a herpes virus that is a very common pathogen in humans. It infects over 80% of people at some point in their lives and often we do not even notice the infection. The virus remains dormant in the body, but does not cause problems unless the carrier's immune system is significantly compromised for some reason. If this happens, the cytomegalovirus may become active and dangerous.

“I was aiming for a career as a transplant surgeon and started working at the Karolinska University Hospital´s transplant unit. Back in the 1980s, cytomegalovirus was a major problem in transplantation. At that time, the virus could not be detected except by tissue culture and it took weeks to obtain the results. If the transplant recipient developed pneumonia, we sent them to intensive care, but usually they never came back. It was back then when I first became curious about this virus,” says Söderberg-Nauclér.

For me, it's about knowledge, not whether I'm right or wrong.

By all accounts, Söderberg-Nauclér was unstoppable in her younger years. The lights in the laboratory stayed on late into the night and the last train home departed often without her.

“I stayed in the lab 3–4 nights a week. I conducted research, assisted at surgery, and studied. Then, after a long day, when a colleague and I were closing a transplant patient, my colleague accidentally stuck a needle in my finger. The needle went all the way into the bone and there I stood, a needle sticking out of my hand. It was a turning point. When I got home, told my husband that, even if I argue otherwise in the future, remind me that I am a researcher, not a surgeon.”

Virus that activates in brain cancer

Next, Söderberg-Nauclér invested in her research career at the Karolinska Institutet and at the Oregon Health Science University in Portland, United States. There were many questions that needed answers: what is the role of cytomegalovirus in organ transplant rejection? What about in chronic inflammatory diseases? How is the virus reactivated from latency? And how big of a role does the virus have in cardiovascular diseases? Success followed, with several publications in top journals.

After fifteen years of researching cytomegalovirus, she thought she knew what the virus was capable of. Then a new fact about the microbe came into light.

“It became evident that cytomegalovirus is also present and active in many cancer tumours and cancer metastases. It is not present in the healthy tissue surrounding the cancer. What is the virus doing in cancer tumours, why is it there?”

At this stage, Söderberg-Nauclér's interest turned to a brain cancer, glioblastoma, in which the cytomegalovirus appears to be active. Glioblastoma is a cancer where hundreds of clinical trials have ended in disappointment. Since 2005, there have been no new really effective treatments available for the disease and the prognosis for patients remains very grim.

Could an antiviral drug provide a solution?

Söderberg-Nauclér wanted to see what happens if a brain cancer patient is given a drug that inhibits viral activity during their treatment.

“We gave the patients valganciclovir, a drug commonly used to treat, for example, retinitis and pneumonitis caused by cytomegalovirus. In the study, the average survival time for brain cancer patients who received the antiviral therapy was 29.7 months, compared to the more general 13–14 months.”

Söderberg-Naucler stresses that valganciclovir is not a cure for brain cancer, but the data is promising. It appears that the drug prevents radiation-induced reactivation of cytomegalovirus, which further prevents early tumour recurrencies.

Funding for further research was difficult to obtain, but now they have closed recruitment of 220 patients with the brain cancer glioblastoma to assess the effect of valganciclovir on tumour progression and survival with grant support from the Swedish Medical Research Council.

The work on understanding the role of this virus in glioblastoma is now progressing with a large grant of €4.2 million from the Lundbeck Foundation in Denmark. It was awarded in early 2025 to the research groups of Söderberg-Nauclér and Danish Professor Jiri Bartek.

Stowaway in the virus

Söderberg-Nauclér believes that cancer is something other than the genetic disease it is commonly thought to be. She thinks that the root cause of cancer lies in metabolism. This may be proven by the fact that if a nucleus of a cancer cell with its genetic codes is transferred to a cell with a normal metabolic environment, nothing bad happens.

But what does this have to do with cytomegalovirus?

"Our data implies that only a certain type of cytomegalovirus is strongly associated with cancer. We are currently studying its effect on cellular metabolism. Cancer cells use carbohydrates, proteins and fats either from food or from the body's energy stores, and produce energy differently from normal cells.”

The altered metabolism of cancer cells is known as the Warburg effect, and is caused by changes in mitochondria functions. Mitochondria burn food for energy and to create materials for cell building – they are the "power plants" of the cell.

“Cancer cells exhibit the Warburg effect and make energy in a different way, we just don't know yet how cells switch from normal metabolism to the Warburg effect. Studying how cytomegalovirus causes the Warburg effect gave us unexpected insights and revealed energy-making routes in cancer that have been so far overlooked. This could open for new cancer treatments.”

I would argue that in about ten years' time, the scientific community and pharmaceutical companies will be investing in research into cancer metabolism and seeking new treatments.

Söderberg-Nauclér's theory is that this particular variant of cytomegalovirus carries another virus, a stowaway, which could provide the link to cellular metabolism and cancer.

“For me, it's about knowledge, not whether I'm right or wrong. My theory goes against the established view of cancer and is very controversial, but you have to remember that immunological treatments for cancer, for example, were not believed in twenty years ago, and now they are at the centre of investigation. I would argue that in about ten years' time, the scientific community and pharmaceutical companies will be highly focused on investing in research into cancer metabolism and seeking new treatments.”

Turku has given peace of mind

Söderberg-Nauclér was appointed as a professor to the University of Turku and its InFLAMES research flagship in 2022. She spends 3–5 days a week at the MediCity Laboratory at BioCity, leading her own team, which she considers to be the best team she has ever had. She also says the research environment in Turku is excellent. For someone used to the size and bureaucracy of the Karolinska Institutet, the proximity of everything in Turku is new and energising.

“I am so grateful for the opportunity and for the kind welcome I have received here. Everyone has been very helpful.”

Söderberg-Nauclér admits that Turku gave her the peace of mind that had suffered in Sweden. She disagreed with Sweden's official line on the COVID-19 pandemic and considered it her duty to contribute to the debate. Dissidents were not treated well, and the debate on social media escalated into a smear campaign, which led her to closing her Twitter account, among other things.

She does not regret what she said. She says the epidemic forecast she and her colleagues made was right on point, except for one thing. No one took into account the immune protection that especially the people in Nordic countries had from the swine flu. The clue—that something was protecting people—came from observations in Sweden.

Her team then identified specific cross-protection from swine flu tied to HLA types common in the region, which conferred unusually strong protection. Because of this stroke of luck, Söderberg-Nauclér says that no country should take a cue from Sweden's approach to dealing with a pandemic in the future.

Söderberg-Nauclér's home and family, her husband, three grown-up children and their corgi, are in Stockholm. She sometimes finds leaving for the Turku airplane or ferry to be tiring, but once she reaches her destination, her energy is renewed and the days pass in a flash. Söderberg-Nauclér has always worked long hours and she continues do so in Turku, too. For her, being a researcher is a way of life and she hopes to be a role model for her team members.

Söderberg-Nauclér could well imagine living in Turku, but for the time being, the trips across the Baltic Sea continue.

“When I return home and my husband asks me how was Turku, I often reply that unfortunately it was great!”

Text: Liisa Koivula

Translation: Mari Ratia

Photos: Hanna Oksanen